As the world seeks to transition toward a sustainable energy future, hydrogen is rapidly gaining prominence as a versatile and clean energy carrier. Its unique ability to decarbonize various sectors—from heavy industry and transportation to power generation—positions hydrogen as a cornerstone of global decarbonization efforts. Unlike other energy carriers, hydrogen’s applications span a wide range of industries and processes, offering solutions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in sectors that are difficult to electrify. However, realizing hydrogen’s full potential requires a comprehensive understanding of its value chain, which encompasses production, storage, transportation, and utilization. Each step in this intricate network presents both challenges and opportunities that must be addressed to unlock hydrogen’s role in building a sustainable, low-carbon economy.

This article delves into the key components of the hydrogen value chain, exploring its production methods, storage solutions, transportation systems, and end-use applications. By shedding light on the technical and economic considerations associated with hydrogen, this guide aims to provide stakeholders with the knowledge necessary to navigate the complexities of this emerging energy paradigm. From the innovative technologies driving advancements in hydrogen production to the regional strategies shaping its global adoption, this comprehensive overview highlights hydrogen’s transformative potential in achieving a net-zero future.

Companion Content: See Hydrogen in the Energy Transition: Key Projects and Critical Insights for additional information on the subject of Hydrogen.

Hydrogen Production: The Starting Point

The production of hydrogen is the foundation of the value chain and determines its environmental impact, scalability, and economic viability. Hydrogen can be produced through a variety of methods, each of which carries a unique set of characteristics. These production methods are often categorized by "colors" to denote their carbon intensity, ranging from gray hydrogen, which is fossil-fuel-based and emits significant CO₂, to green hydrogen, which is produced using renewable energy with zero emissions. Understanding these distinctions is essential for selecting the appropriate production technology for specific applications and markets.

Hydrogen Production Methods

Color | Production Method | Feedstock | Carbon Emissions | Cost ($/kg) |

Gray Hydrogen | Steam Methane Reforming (SMR) | Natural Gas | High | $1–2 |

Natural Gas | Moderate (CO₂ captured) | $2–3 | ||

Green Hydrogen | Electrolysis (Renewable Electricity) | Water + Renewable Energy | Zero | $3–6 |

Turquoise Hydrogen | Methane Pyrolysis | Natural Gas | Low (Solid Carbon Byproduct) | $2–4 |

Pink Hydrogen | Electrolysis (Nuclear Electricity) | Water + Nuclear Energy | Zero | $3–5 |

Note: There are other production methods for hydrogen that are not shown here. The methods shown are the most common.

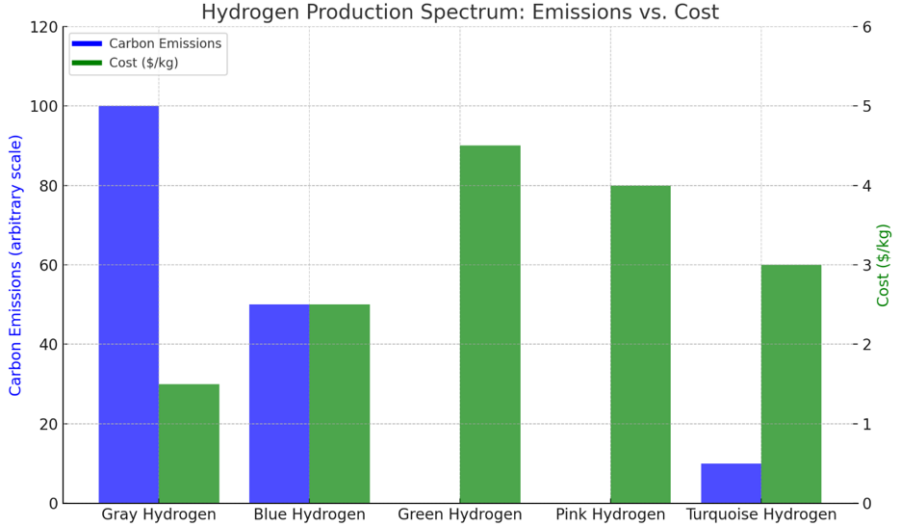

Hydrogen Production Spectrum: Emissions vs. Cost

This chart compares the carbon emissions and costs associated with various hydrogen production methods, highlighting the trade-offs in the hydrogen production spectrum.

Gray hydrogen, produced from natural gas without carbon capture, exhibits the highest carbon emissions but relatively low production costs.

Blue hydrogen, which incorporates carbon capture technology, reduces emissions significantly while maintaining moderate costs.

Green hydrogen, generated through electrolysis powered by renewable energy, achieves near-zero emissions but comes at a higher cost per kilogram.

Pink hydrogen, produced via electrolysis using nuclear energy, also maintains low emissions with similar cost challenges to green hydrogen.

Turquoise hydrogen, derived from methane pyrolysis, shows minimal emissions with lower costs, making it a promising emerging option.

This spectrum underscores the varying economic and environmental impacts of hydrogen production technologies, helping stakeholders evaluate suitable approaches for achieving decarbonization goals.

Hydrogen Storage: Meeting the Density Challenge

Storing hydrogen presents a unique set of technical challenges due to its physical properties. As the lightest element, hydrogen has a very low volumetric energy density, meaning it must be compressed, liquefied, or chemically bonded to other carriers for practical storage and transportation. Each storage method has specific advantages, limitations, and costs, and the choice of method often depends on the intended application, available infrastructure, and economic constraints.

Example:

Hydrogen gas is commonly stored at pressures between 3,000 psig and 10,000 psig in high-pressure cylinders. For liquid hydrogen, cryogenic tanks are used, requiring temperatures as low as -423°F (-253°C) to maintain a liquid state.

Hydrogen Storage Methods

Method | Description | Advantages | Challenges |

Compressed Hydrogen | Stored in high-pressure tanks (350–700 bar); (5,076 – 10,153 psig) | Low equipment cost | High energy for compression; Low energy density |

Liquid Hydrogen | Stored at cryogenic temperatures (-423°F) | High energy density | Energy-intensive liquefaction |

Ammonia/LOHCs | Hydrogen stored chemically as ammonia or in liquid organic hydrogen carriers (LOHCs) | Easier to transport | Requires reconversion to H₂ |

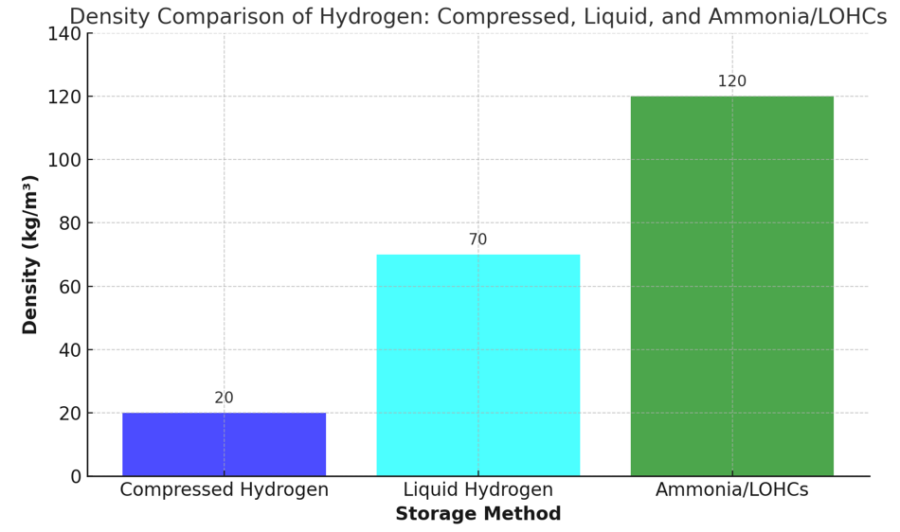

Density Comparison of Hydrogen: Compressed, Liquid, and Ammonia/LOHCs

This chart illustrates the density comparison of hydrogen across three common storage methods: compressed hydrogen, liquid hydrogen, and hydrogen stored as ammonia or in liquid organic hydrogen carriers (LOHCs).

Compressed hydrogen: typically stored at high pressures (e.g., 350-700 bar), has the lowest density of approximately 20 kg/m³, making it suitable for applications where weight and portability are critical, such as fuel cell vehicles.

Liquid hydrogen: achieved by cooling hydrogen to cryogenic temperatures -423°F (-253°C), offers a significantly higher density of 70 kg/m³, improving energy storage efficiency but requiring complex insulation and energy-intensive liquefaction processes.

Ammonia or LOHCs: provide the highest density at 120 kg/m³, leveraging chemical storage for long-term or large-scale hydrogen transport and distribution.

This comparison highlights the trade-offs in storage method selection, balancing density, energy requirements, and practical applications in the hydrogen supply chain.

Hydrogen Transportation: Moving Hydrogen to End Users

Transportation is a critical link in the hydrogen value chain, bridging the gap between production facilities and end-use applications. The mode of transportation depends on factors such as distance (e.g., miles or kilometers), volume, and the form of hydrogen being transported (e.g., gas, liquid, or a chemical carrier). Pipelines are commonly used for short to medium distances, while ships and rail are preferred for long-distance or large-scale transport. However, hydrogen’s properties, including its low density and potential for embrittlement, add layers of complexity to its transportation, requiring specialized solutions.

Hydrogen Transportation Methods and Costs

Method | Cost | Best Use | Key Challenge |

Pipelines (Gaseous) | $1–2 | Large volumes, short distances | Retrofitting pipelines for H₂ handling |

Trucks/Rail (Gaseous / Liquid) | $3–6 | Moderate distances | Limited payload capacity; infrastructure |

Shipping (Ammonia) | $5–7 | Long distances, export | Energy loss during ammonia conversion |

Hydrogen Challenges vs. Opportunities

As hydrogen scales up to meet the demands of the energy transition, its adoption faces significant hurdles. High production costs, limited infrastructure, and technical challenges in storage and transportation have slowed hydrogen’s widespread implementation. However, these challenges also create opportunities for innovation, policy interventions, and technological advancements. By addressing these barriers, hydrogen can become a key driver of decarbonization and a cornerstone of global energy systems.

Challenge | Opportunity/Solution |

High costs of green hydrogen production | Lower renewable energy costs, advanced electrolyzers, government subsidies |

Retrofitting pipelines for pure hydrogen | Blending hydrogen with natural gas as a transitional solution |

Safety risks in storage and transport | Advanced materials for embrittlement resistance and stricter protocols |

Scaling hydrogen infrastructure | Public-private partnerships to accelerate refueling and pipeline networks |

Hydrogen Distribution: Connecting Supply to Demand

Hydrogen distribution systems are a cornerstone of the hydrogen economy, ensuring that this versatile energy carrier can reach end-users efficiently, reliably, and safely. As hydrogen production scales up to meet increasing global demand, the development of robust, adaptable distribution infrastructure becomes essential for connecting production sites with consumption points across various sectors.

As discussed, hydrogen can be transported through multiple pathways, each tailored to specific market needs and logistical challenges. Pipelines are the most efficient and cost-effective method for large-scale, centralized hydrogen distribution, particularly for industrial hubs and regions with concentrated hydrogen demand. These pipelines can also be retrofitted from existing natural gas networks, reducing the upfront costs of infrastructure development. However, pipeline deployment requires significant upfront investment and is most viable in regions with well-established hydrogen markets.

For regions or applications where pipelines are not feasible, alternative distribution methods like trucks, rail, and shipping come into play. Compressed hydrogen gas can be transported in high-pressure cylinders or tube trailers for relatively short distances, offering flexibility for small-scale users such as research facilities or local fueling stations. Liquid hydrogen, achieved by cryogenic cooling, is more suitable for long-distance transport due to its higher energy density, though it requires specialized insulated containers and careful handling.

Hydrogen’s conversion into derivatives such as ammonia or Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carriers (LOHCs) adds another dimension to distribution strategies. Ammonia and LOHCs provide a more stable and dense means of transporting hydrogen over long distances, particularly for export markets. These carriers can be shipped using existing infrastructure, such as tankers or rail, and then converted back into hydrogen at the destination or used directly in industrial applications. This approach is particularly beneficial for bridging the gap between hydrogen-rich production regions, like those with abundant renewable energy, and import-dependent markets.

Refueling stations represent the final link in the distribution chain, enabling the adoption of hydrogen-powered vehicles in transportation. These stations must be strategically located to support the growth of fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs), including passenger cars, buses, and long-haul trucks. Establishing a widespread refueling network will be critical to fostering consumer confidence and accelerating the adoption of hydrogen in the mobility sector.

As the hydrogen economy grows, the integration and optimization of these distribution methods will play a pivotal role in meeting diverse market demands. Hydrogen distribution infrastructure must be flexible, scalable, and aligned with regional and global supply chains. By investing in innovative solutions and leveraging existing infrastructure where possible, the hydrogen industry can overcome logistical challenges and build a robust network that connects supply to demand, ensuring hydrogen’s role as a key enabler of the global energy transition.

Hydrogen Regional Strategies

Different regions are adopting hydrogen strategies tailored to their unique strengths and needs. For instance, Europe is leveraging its renewable energy resources to focus on green hydrogen, while countries in the Middle East are capitalizing on their abundant natural gas supplies to produce blue hydrogen for export.

Region | Key Strategy | Focus Areas |

Europe | EU Green Hydrogen Strategy | 40 GW of electrolyzers by 2030 |

United States | Hydrogen Tax Credits under Inflation Reduction Act | Green hydrogen production and infrastructure |

Japan | Hydrogen Society | Fuel cell vehicles and hydrogen imports |

Middle East | Green Hydrogen for Export | Large-scale ammonia hubs for global markets |

Hydrogen Emerging Technologies

Hydrogen’s versatility makes it a unique energy carrier with applications that extend beyond traditional uses. As innovation progresses, hydrogen is being explored in sectors that were previously considered challenging to decarbonize, opening up new possibilities for its adoption.

Hydrogen in Aviation

The aviation sector contributes significantly to global greenhouse gas emissions, making it a critical target for decarbonization. Hydrogen-powered aviation is rapidly gaining attention as a feasible alternative to fossil-fueled aircraft.

- Hydrogen Fuel Cells:

- Hydrogen fuel cells generate electricity to power electric motors in smaller aircraft.

- Example: Airbus is developing hydrogen-powered aircraft with a target of entering service by 2035.

- Direct Hydrogen Combustion:

- Combusting hydrogen in gas turbines for larger planes can achieve zero CO₂ emissions, with only water vapor as a byproduct.

- Challenges:

- Storing liquid hydrogen at cryogenic temperatures on aircraft requires specialized tank designs.

- Developing a global refueling infrastructure for airports.

Hydrogen for Maritime Shipping

Shipping is another hard-to-abate sector where hydrogen and its derivatives, such as ammonia, can provide a sustainable fuel alternative.

- Ammonia as Fuel:

- Ammonia, derived from hydrogen, is easier to store and transport than hydrogen gas and is being explored as a primary fuel for ships.

- Example: Companies like Maersk are developing ammonia-powered vessels to meet global decarbonization targets.

- Hydrogen Combustion Engines:

- Hydrogen can be used in modified combustion engines to power ships, offering a cleaner alternative to bunker fuels.

- Challenges:

- Addressing ammonia’s toxicity during handling and ensuring sufficient hydrogen production for large-scale adoption.

Hydrogen Blending in Natural Gas Pipelines

Hydrogen blending involves mixing hydrogen with natural gas in existing pipeline infrastructure, providing an interim solution for hydrogen transport and usage.

- Advantages:

- Reduces the carbon footprint of natural gas while utilizing existing infrastructure.

- Hydrogen blends of up to 20% by volume are being implemented in several pilot projects globally.

- Challenges:

- Hydrogen embrittlement in pipelines and the need for infrastructure upgrades to accommodate higher concentrations.

Hydrogen in Steel and Cement Production

Industries like steel and cement are among the largest emitters of CO₂ due to their reliance on carbon-intensive processes.

- Steel:

- Hydrogen can replace coking coal in Direct Reduced Iron (DRI) processes to produce green steel.

- Example: Companies like ArcelorMittal and SSAB are piloting hydrogen-based steel production plants.

- Cement:

- Hydrogen can serve as a heat source in kilns, reducing reliance on coal or natural gas.

Technological advancements are reshaping the hydrogen value chain, making production, storage, and transportation more efficient and cost-effective.

Hydrogen Technology Advancement Opportunities

Technology | Description | Impact |

Advanced Electrolyzers | PEM and solid oxide electrolyzers with higher efficiencies | Reduce green hydrogen costs |

Ammonia Cracking Technologies | Efficient reconversion of ammonia back to hydrogen | Enables global hydrogen trade |

Metal Hydride Storage | Storing hydrogen in solid-state materials | Safer and more compact storage solutions |

Hydrogen-Powered Aviation | Development of hydrogen-fueled aircraft by companies like Airbus | Decarbonizes long-haul flights |

Hydrogen Utilization: The End Goal

Hydrogen’s versatility positions it as a crucial component of a balanced energy future rather than a wholesale replacement for existing energy systems. Its unique ability to decarbonize a broad range of sectors, particularly hard-to-abate industries like steelmaking, cement production, and heavy-duty transportation, underscores its importance. These sectors are difficult to electrify due to their high energy demands and reliance on processes requiring intense heat or dense energy carriers, where hydrogen excels as a clean alternative.

Furthermore, hydrogen serves as a critical enabler for renewable energy integration. By acting as a long-term energy storage solution, hydrogen can capture surplus energy generated by wind and solar during periods of low demand, storing it for later use when renewable output wanes. This capability ensures grid reliability and helps overcome the intermittency challenges of renewables, facilitating the transition to a more sustainable energy system.

However, hydrogen is not a silver bullet for decarbonization. It will play a complementary role alongside other clean technologies, such as battery storage, electrification, and biofuels, creating a balanced and resilient energy ecosystem. For example, while batteries may dominate short-term energy storage and passenger vehicle applications, hydrogen will shine in long-term storage, industrial processes, and long-haul transportation.

The end goal is not to replace existing systems with hydrogen alone but to integrate it thoughtfully where its properties provide the greatest value. This balanced approach ensures a diverse, secure, and efficient energy transition that leverages the strengths of all available technologies to meet global climate goals.

Hydrogen Projections and Market Growth

The hydrogen market is set to experience exponential growth in the coming decades, fueled by a confluence of factors including increasing global investments, rapid technological advancements, and robust policy support from governments worldwide. Hydrogen’s potential to play a transformative role in the global energy transition has positioned it as a cornerstone of future clean energy systems, with applications spanning energy storage, transportation, industry, and power generation.

Current market projections suggest that by 2050, hydrogen could supply up to 20% of the world’s total energy demand, a significant leap from its relatively niche position today. This shift is expected to contribute to reducing CO₂ emissions by billions of tons annually, particularly in hard-to-abate sectors such as steelmaking, chemicals production, shipping, and aviation. By replacing fossil fuels in these areas, hydrogen can help bridge the gap to achieving net-zero emissions targets while maintaining economic competitiveness and industrial productivity.

Global investments in hydrogen infrastructure and production capacity are accelerating, with major economies such as the European Union, Japan, South Korea, and the United States unveiling ambitious hydrogen strategies. These plans include substantial financial commitments toward research, development, and deployment of hydrogen technologies, as well as the creation of hydrogen production hubs and international trade networks. For instance, the European Union’s Green Hydrogen Initiative aims to produce millions of tons of green hydrogen annually by 2030, primarily using renewable energy sources such as wind and solar.

Technological advancements are another key driver of market growth. Innovations in electrolysis, which produces hydrogen from water using electricity, are reducing costs and improving efficiency, making green hydrogen increasingly competitive with traditional fossil-based production methods. Similarly, advancements in carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology are enabling the scale-up of blue hydrogen, which involves producing hydrogen from natural gas with minimal emissions. Emerging technologies such as methane pyrolysis (for turquoise hydrogen) and hydrogen storage solutions are further expanding the scope and feasibility of hydrogen applications.

Supportive policies and regulatory frameworks are also shaping the market’s trajectory. Carbon pricing, renewable energy mandates, and clean energy incentives are creating favorable conditions for hydrogen adoption. International collaboration on standards and certifications is helping to establish a global hydrogen market, enabling trade between regions with abundant renewable resources and those with high hydrogen demand.

By 2030, the hydrogen market is expected to reach significant milestones, including cost reductions that make green hydrogen competitive in key applications and the establishment of a widespread hydrogen refueling infrastructure. By mid-century, hydrogen could become a mainstream energy carrier, integrated seamlessly into a balanced mix of renewable energy sources, electrification, and other clean technologies.

Ultimately, the projected growth of hydrogen represents more than just market expansion—it signifies a paradigm shift in how energy is produced, transported, and consumed. With its ability to decarbonize multiple sectors and provide long-term energy storage, hydrogen is not just an emerging player but a pivotal force in achieving a sustainable and resilient global energy system.

Market Growth by the Numbers

Global Hydrogen Demand:

The International Energy Agency (IEA) projects that global hydrogen demand could increase from approximately 95 million tonnes (Mt) in 2022 to around 430 Mt by 2050 under the Net Zero Emissions by 2050 Scenario.

Source: IEA

Regional Market Growth:

According to forecasts, Europe’s hydrogen demand is expected to grow from 20 Mt in 2030 to 95 Mt in 2050, maintaining a 14% share of the global demand.

Source: Statista

Clean Hydrogen Market Value:

The global market size for clean hydrogen is projected to expand from $642 billion in 2030 to over $1.4 trillion by 2050.

Source: Statista

Hydrogen’s Share in Total Energy Consumption:

Estimates suggest that hydrogen could account for 6% to 25% of total final energy consumption by 2050, depending on various scenarios and underlying assumptions.

Source: World Energy Council

Sectoral Demand Distribution:

By 2050, the distribution of hydrogen demand across different sectors is expected to be:

- Industry: 139 Mt

- Transport: 193 Mt (including hydrogen-based fuels)

- Power Generation: 74 Mt (including hydrogen-based fuels)

- Other Uses: 14 Mt

Source: IEA

Hydrogen’s Role in Decarbonization

Hydrogen is a cornerstone of global decarbonization strategies, offering solutions to reduce emissions in sectors that are challenging to electrify. Its role spans energy production, industrial processes, transportation, and power storage, making it indispensable for achieving net-zero goals.

Stabilizing Renewable Energy Grids

The intermittency of renewable energy sources like wind and solar poses challenges for grid reliability. Hydrogen acts as a bridge, storing excess renewable energy for later use.

- Electrolyzers for Energy Storage:

During periods of excess wind or solar generation, electrolyzers convert electricity into hydrogen, which can be stored and reconverted to electricity when needed.- Example: Germany’s power-to-gas projects integrate hydrogen storage into the national grid.

- Seasonal Storage:

Unlike batteries, hydrogen can store energy for months, making it ideal for addressing seasonal demand fluctuations.

Decarbonizing Transportation

Hydrogen plays a critical role in decarbonizing heavy-duty and long-distance transportation, where battery-electric solutions are often impractical.

- Fuel Cell Vehicles (FCVs):

Hydrogen fuel cells power electric motors in vehicles, emitting only water vapor as a byproduct.- Example: Toyota’s Mirai and Hyundai’s Nexo lead the FCV market for passenger vehicles.

- Heavy-Duty Applications:

Hydrogen powers trucks, buses, and trains, particularly in regions with long-haul routes or where electrification infrastructure is limited.

Industrial Decarbonization

Hydrogen can replace fossil fuels in industrial processes, significantly reducing CO₂ emissions in energy-intensive industries.

- Ammonia Production:

Switching from gray hydrogen to green hydrogen in ammonia production eliminates a significant source of industrial emissions. - Refineries:

Hydrogen is used in refining processes like hydrocracking and desulfurization. Replacing gray hydrogen with green hydrogen can substantially reduce emissions.

Carbon Capture and Blue Hydrogen

Blue hydrogen, produced through steam methane reforming (SMR) with carbon capture, serves as an important transitional strategy.

- Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS):

Captures up to 90% of CO₂ emissions from hydrogen production, enabling lower-carbon solutions while green hydrogen scales up. - Infrastructure Synergies:

Regions with existing natural gas infrastructure and geological storage capacity for CO₂ are well-positioned to adopt blue hydrogen.

Hydrogen in Energy Export Markets

Hydrogen and its derivatives are set to become global commodities, enabling countries rich in renewable resources to export clean energy.

- Green Ammonia Exports:

Countries like Australia and Saudi Arabia are positioning themselves as major exporters of green ammonia to meet European and Asian demand. - Hydrogen as a Global Trade Commodity:

Hydrogen hubs connected by pipelines and shipping lanes are forming the backbone of a future hydrogen economy.

Technical and Practical Insights for Engineers

Electrolyzers: The Heart of Green Hydrogen Production

Electrolyzers are critical to producing green hydrogen, using electricity to split water into hydrogen and oxygen. There are three primary types of electrolyzers, each suited for specific applications and scales of operation:

Electrolyzer Type | Description | Key Advantages | Challenges |

Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM) | Utilizes a solid polymer electrolyte for ion conduction. Operates at high current densities. | Compact, high efficiency, quick startup | High cost of platinum-based catalysts |

Alkaline | Uses liquid potassium hydroxide as the electrolyte, with nickel-based electrodes. | Low cost, well-established technology | Lower efficiency, larger footprint |

Solid Oxide (SOEC) | Operates at high temperatures (~700–1,000°C), splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen efficiently. | Highest efficiency, integrates with waste heat sources | High operating temperatures and durability concerns |

Technical Insights:

- Operating Pressure: Most commercial electrolyzers operate at pressures of 15–30 bar (217–435 psig) to reduce downstream compression costs for storage or transport.

- Efficiency: PEM electrolyzers achieve 65–75% efficiency, while SOEC systems can exceed 80% efficiency when integrated with heat recovery.

- Innovations: Emerging technologies include non-precious metal catalysts and modular electrolyzers for scalability.

Ammonia Production: A Critical Step for Hydrogen Transport

Ammonia (NH₃) is a vital hydrogen carrier due to its higher volumetric energy density and ease of liquefaction compared to hydrogen gas. Ammonia is primarily produced through the Haber-Bosch process, which combines hydrogen and nitrogen under high pressure and temperature in the presence of a catalyst.

Production Process:

- Hydrogen Source: Hydrogen is typically sourced from steam methane reforming (SMR), partial oxidation of hydrocarbons, or water electrolysis.

- Nitrogen Source: Nitrogen is obtained from air through cryogenic distillation or pressure swing adsorption (PSA).

- Reaction: Hydrogen and nitrogen are combined in a 3:1 molar ratio in the Haber-Bosch reactor:

N₂ + 3H₂ → 2NH₃ + heat (exothermic reaction)- Conditions: 150–250 bar (2,175–3,625 psig) and 400–500°C (752–932°F).

- Catalyst: Iron-based catalysts with promoters like potassium or aluminum oxides.

Key Insights:

- Energy Consumption: The Haber-Bosch process is energy-intensive, consuming approximately 9–12 MWh per ton of ammonia.

- Efficiency: Advances in catalyst technology and process integration (e.g., using renewable electricity) are improving efficiency.

- Green Ammonia: Green hydrogen from electrolysis, combined with renewable energy, is increasingly used to produce ammonia with near-zero emissions.

Applications of Ammonia:

- Hydrogen Transport: Ammonia serves as an efficient carrier for hydrogen over long distances due to its ease of liquefaction at -33°C (-27.4°F) or moderate pressures (~10–15 bar).

- Fertilizers: Ammonia is a key ingredient in nitrogen-based fertilizers like urea and ammonium nitrate.

- Energy Storage and Fuel: Emerging technologies are exploring ammonia as a direct fuel for power generation and maritime shipping.

Ammonia Cracking: Unlocking Hydrogen for Export

Ammonia cracking involves converting ammonia back into hydrogen and nitrogen at the destination.

Cracking Process:

- Reaction: 2NH₃ → N₂ + 3H₂ (endothermic process).

- Catalysts: Nickel-based catalysts facilitate cracking at temperatures between 500°C and 700°C (932°F to 1,292°F).

- Purity Challenges: The resulting hydrogen often contains trace amounts of ammonia, which must be removed to meet fuel cell purity standards (<0.1 ppm).

Engineering Considerations:

- Energy Efficiency: Cracking requires significant thermal input, often sourced from renewable electricity or waste heat.

- Integration with Fuel Cells: Direct cracking near end-use applications reduces transport complexity and costs.

Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carriers (LOHCs): A Promising Storage Solution

LOHCs are chemicals that can reversibly absorb and release hydrogen, enabling safe storage and transport under ambient conditions. Common LOHCs include toluene and dibenzyl toluene.

How LOHCs Work:

- Hydrogenation: Hydrogen is chemically bonded to the carrier at production sites.

- Conditions: ~300°C (572°F) and 30–50 bar (435–725 psig).

- Dehydrogenation: Hydrogen is released at the destination.

- Conditions: ~250°C (482°F) and ambient pressure.

Advantages:

- Safe Handling: LOHCs are non-flammable and can use existing liquid fuel infrastructure.

- Reusability: The carrier liquid can be cycled hundreds of times.

Challenges:

- Efficiency Loss: ~20–30% of hydrogen’s energy is consumed during hydrogenation and dehydrogenation.

- Catalyst Development: Requires robust catalysts for efficient operation over multiple cycles.

Pressure and Temperature Requirements for Hydrogen Storage and Transport

Hydrogen’s low molecular weight and high flammability demand careful management of pressure and temperature to ensure safety and efficiency. Engineers must design systems tailored to the specific form of hydrogen being stored or transported.

Form | Storage/Transport Conditions | Applications |

Compressed Hydrogen | Pressures of 3,000–10,000 psig (200–700 bar). Typically stored in high-pressure cylinders or composite tanks. | Short-distance transport, refueling stations. |

Liquid Hydrogen | Stored at cryogenic temperatures of -423°F (-253°C) in insulated tanks to maintain its liquid state. | Long-distance shipping, aerospace. |

Ammonia | Stored as a liquid under 10–15 bar (145–218 psig) at -33°C (-27.4°F) or at atmospheric pressure when refrigerated. | Export and bulk storage. |

LOHCs | Stored at ambient temperature and pressure. Hydrogen is chemically bonded to the carrier liquid. | Safe transport over long distances. |

Design Challenges:

- Cryogenic Storage:

- Insulated tanks minimize boil-off losses but require robust materials to handle thermal stress.

- Applications like space exploration use liquid hydrogen for its high energy density.

- High-Pressure Systems:

- Composite materials, such as carbon fiber, reduce the weight of storage tanks.

- Refueling stations operate at pressures up to 700 bar (10,000 psig) for vehicle applications.

- Safety Mechanisms:

- Pressure relief valves and venting systems prevent overpressure incidents.

- Continuous monitoring systems detect leaks and prevent hydrogen embrittlement.

Conclusion

The hydrogen value chain holds immense potential to revolutionize the global energy landscape, serving as a vital enabler of decarbonization in key sectors. From its production through renewable energy sources to its utilization in heavy industry, transportation, and energy storage, hydrogen offers a versatile and scalable solution to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. While challenges such as high production costs, limited infrastructure, and technical barriers persist, these obstacles also create opportunities for innovation, collaboration, and investment.

As governments, industries, and research institutions continue to align efforts, hydrogen is poised to play a pivotal role in addressing the energy trilemma of affordability, reliability, and sustainability. By advancing technologies, implementing supportive policies, and fostering international cooperation, stakeholders can accelerate the development of a robust hydrogen economy. Ultimately, hydrogen’s success in the global energy transition will depend on overcoming these barriers and capitalizing on its unique attributes to create a cleaner, more resilient energy system for future generations. The journey toward a hydrogen-powered future is not without its challenges, but it promises transformative benefits that will redefine the way we produce, store, and consume energy across the globe.

Glossary of Key Terms

Alkaline Electrolyzer

A type of electrolyzer using liquid potassium hydroxide as an electrolyte, with nickel-based electrodes. Known for its low cost and well-established technology but has lower efficiency compared to other types.

Ammonia (NH₃)

A hydrogen carrier with higher volumetric energy density than hydrogen gas, making it easier to transport and store. Widely used in fertilizers and emerging as a sustainable fuel for power generation and maritime shipping.

Ammonia Cracking

The process of converting ammonia back into hydrogen and nitrogen through an endothermic reaction using nickel-based catalysts at high temperatures.

Blue Hydrogen

Hydrogen produced through Steam Methane Reforming (SMR) with Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) technology. Offers lower emissions compared to gray hydrogen but is not entirely emissions-free.

Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS)

A process that captures up to 90% of CO₂ emissions from industrial processes, including hydrogen production, and stores it underground to prevent atmospheric release.

Compressed Hydrogen

Hydrogen stored under high pressure (typically 3,000–10,000 psig or 200–700 bar) in high-pressure tanks. Suitable for short-distance transportation and refueling stations.

Direct Reduced Iron (DRI)

A steel production process where hydrogen can replace coking coal to produce green steel with significantly reduced carbon emissions.

Electrolysis

A process that uses electricity to split water into hydrogen and oxygen, central to green hydrogen production.

Fuel Cell Vehicle (FCV)

A vehicle powered by hydrogen fuel cells, which generate electricity to drive electric motors, emitting only water vapor as a byproduct.

Gray Hydrogen

Hydrogen produced from fossil fuels, primarily through SMR, emitting significant CO₂ and representing the most carbon-intensive form of hydrogen.

Green Hydrogen

Hydrogen produced using renewable electricity in an electrolysis process, generating zero emissions. It is central to global decarbonization strategies.

Haber-Bosch Process

An industrial method for producing ammonia by combining hydrogen and nitrogen under high pressure and temperature in the presence of a catalyst.

Hydrogen Blending

The process of mixing hydrogen with natural gas in existing pipeline infrastructure, providing an interim solution for hydrogen transport and usage.

Hydrogen Embrittlement

A phenomenon where hydrogen weakens metals by making them brittle, posing challenges for hydrogen storage and transport infrastructure.

Liquid Hydrogen (LH₂)

Hydrogen cooled to cryogenic temperatures (-423°F or -253°C) and stored as a liquid. Offers high energy density but requires energy-intensive liquefaction.

Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carriers (LOHCs)

Chemical compounds, such as toluene, that reversibly bind hydrogen for safe transport and storage under ambient conditions.

Pink Hydrogen

Hydrogen produced via electrolysis powered by nuclear energy, characterized by zero carbon emissions.

Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM) Electrolyzer

An electrolyzer using a solid polymer electrolyte, offering compact size, high efficiency, and fast startup but reliant on expensive platinum-based catalysts.

Seasonal Storage

The ability to store hydrogen for long periods (months), making it ideal for balancing renewable energy supply and demand during seasonal fluctuations.

Solid Oxide Electrolyzer (SOEC)

A high-temperature electrolyzer (~700–1,000°C) that achieves the highest efficiency when integrated with waste heat sources.

Steam Methane Reforming (SMR)

A widely used method for hydrogen production, where natural gas reacts with steam to produce hydrogen and CO₂.

Turquoise Hydrogen

Hydrogen produced via methane pyrolysis, resulting in a solid carbon byproduct, with low emissions compared to gray or blue hydrogen.

Hydrogen Conversion Calculator

Calculator Assumes:

Gas volumes are measured at 1 atmosphere and 70°F.

Liquid volumes are measured at 1 atmosphere and the boiling temperature of the substance.

Disclaimer

The information provided in this post is for reference purposes only and is intended to serve as a guide to highlight key topics, considerations, and best practices. It does not constitute professional advice or a substitute for consulting regarding specific projects or circumstances. Readers are encouraged to evaluate their unique project needs and seek tailored advice where necessary. Please Contact Us to discuss your particular project.